Bloodsuckers: 7 Things You Should Know About the Mosquito

Although the summer may be winding down, mosquito season is still upon us. Typically, the season goes from April to November in the Bay Area. This summer, Stanford Blood Center received quite a few interesting questions from blood donors about mosquitos. We thought we’d take a moment to compile our answers to those questions and, in the process, share some interesting facts about these pesky critters:

……….

1. Do mosquitos have an impact on blood safety?

Yes. Mosquitos can transmit bloodborne illnesses, which may then be transmitted through blood transfusion. Some examples include malaria, West Nile virus (WNV) and Zika virus. Aedes mosquitos are the most common mosquito species in California, and Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus can transmit West Nile virus and Zika virus. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) actively monitors where these two mosquitos species are distributed within the state. (See more at https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/AedesDistributionMap.pdf).

The FDA requires that U.S. blood centers screen all blood donors year-round for WNV and Zika virus. Donors who test positive are informed so they can follow up with their doctor, and they cannot donate blood for 120 days. Blood centers must inform CDPH of any blood donors who test positive since CDPH tracks human cases of WNV and Zika in California. Year to date in California, there have been 62 human cases of WNV, and a small percentage of these cases were asymptomatic blood donors who tested positive as part of routine blood screening. Cases of Zika infection have fortunately significantly decreased since 2016, but blood donor screening is still performed to ensure blood safety.

Malaria is another mosquito-borne illness that may be transmitted through blood transfusion. Currently there is no FDA-approved test for blood donor malaria screening. Thus, U.S. blood centers defer donors who have a history of malaria or who have recently travelled to or lived in an area that is endemic for malaria, such as India or Brazil. This is one reason why we ask blood donors questions about recent travels — although we do enjoy hearing about all the interesting places donors have visited! At Stanford Blood Center, travel to a malaria-endemic region is one of the most common deferrals.

……….

2. If I traveled to a malaria-risk region in the last three months but did not get any mosquito bites or I took malaria prophylaxis, can I donate blood without deferral?

No. Although the risk is lower in people who took prophylactic medication, it is not nonexistent. Also, some people may not know they were bitten by a mosquito so we cannot rely on bite history.

……….

3. Are mosquitos attracted to certain blood types?

Yes. There are studies showing that mosquitos prefer biting people with certain blood types, but it does vary by mosquito species. For example, studies show that Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitos (both found in California; see question one above) have a preference for blood type O. Another species of mosquito that can transmit malaria in Asia has a preference for blood type AB. One study hypothesized that the preference of this mosquito for AB might increase infection and fatality in people with AB blood type, and resultingly may be one reason for the lower frequency of AB blood type in people from some malaria-risk regions.

……….

4. Do certain blood types protect you from illnesses carried by mosquitos?

Yes, but not necessarily the A, B and O blood types that we are all most familiar with. In addition to the blood group antigens on red blood cells that result in ABO blood typing, there are other antigens that cause different blood phenotypes. One example is the Duffy type. People can be Duffy “a” and/or Duffy “b” positive; or be negative for Duffy “a” and “b.” One type of malaria is caused when the parasite Plasmodium vivax binds to red blood cells via the Duffy antigen. Thus, people who are Duffy negative are resistant to malaria caused by Plasmodium vivax. In West Africa, Plasmodium vivax infection is essentially absent, since the majority of the population is Duffy negative.

……….

5. Do different mosquitos cause different reactions?

Not all mosquitos are created equal. Most mosquitos bite during dawn and dusk when they are most active. However, some mosquito species are active and bite during the day, like Aedes aegypti.

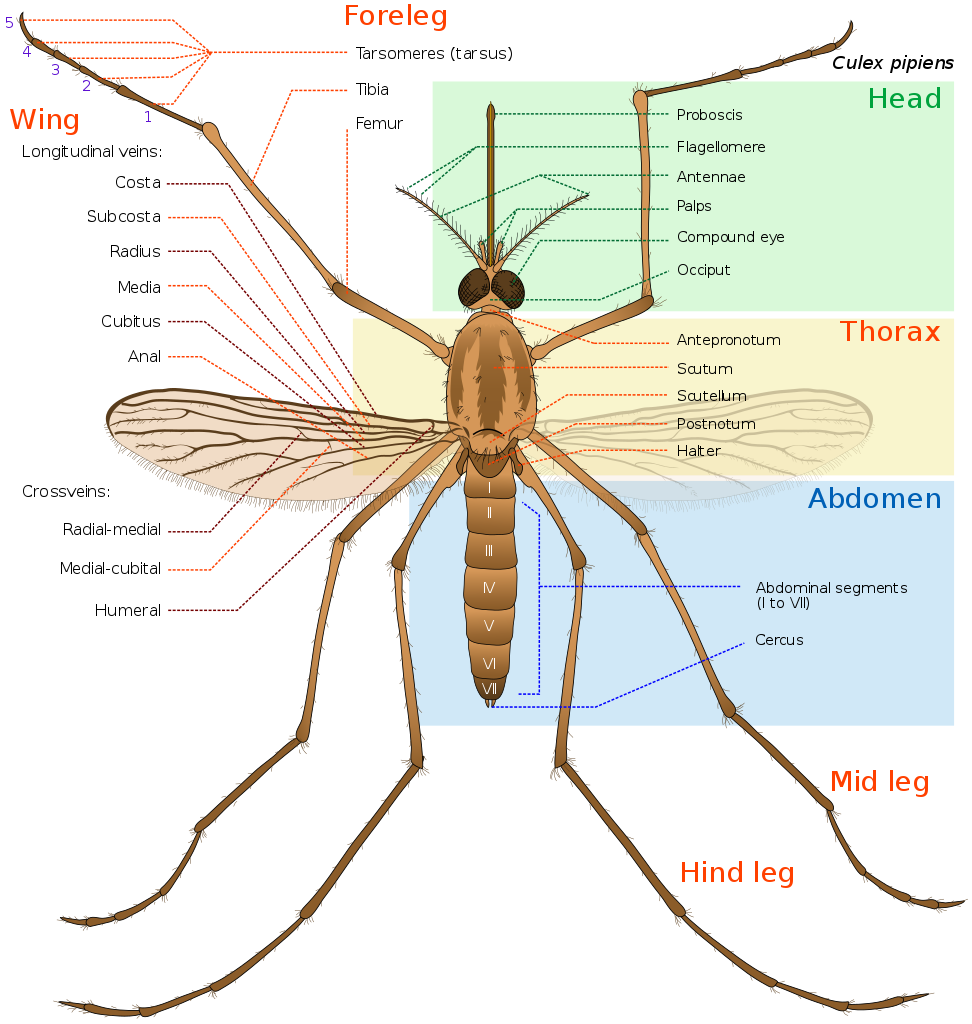

Male mosquitos are harmless and feed only on nectar and water, but female mosquitos require a blood meal since the protein in blood is needed to produce eggs. Heat, light, body odor, carbon dioxide, lactic acid and chemicals in a person’s sweat attract female mosquitos to skin. Female mosquitos have a proboscis (like a snout) which extends from their head and pierces exposed skin to cause a bite. The mosquito releases saliva at the site of the bite.

Most of us are sensitive to mosquito bites and will get a red itchy bump there. This reaction is caused by the human body’s immune system reacting to the protein in the mosquito saliva, not by the bite itself. Contact with a mosquito needs to be held for at least six seconds for a reaction to occur. Redness and puffiness usually develop a few minutes after the bite, and a hard, itchy, red-brown bump appears in the next two days. Some people may also get small blisters and/or dark spots like a bruise. Occasionally, a more severe reaction occurs that causes a large area of redness, swelling and soreness. This is referred to as Skeeter syndrome (think Mo-Skeeter syndrome). It represents a severe allergic reaction to the mosquito saliva and is most common in children. Adults who have had multiple mosquito bites are more desensitized, which makes this reaction less common.

One of the hardest things to do after a bite is NOT TO SCRATCH! Scratching will only prolong the healing and can lead to an infection at the site.

……….

6. Can mosquitos transmit HIV?

Professor Wayne Crans of Rutgers University once aptly said, “Mosquitos are not flying hypodermic needles.” Mosquitos cannot transmit HIV for two main reasons. The first has to do with the mosquito’s blood-sucking anatomy. The proboscis of the mosquito is made up of six parts: four parts are used to pierce the skin when a mosquito bites, and the other two parts are tubes. One tube releases saliva at the bite site and the other sucks the blood. With this two-tube system, only mosquito saliva is injected at the site and no blood contained in the mosquito from prior bites is released. Second, HIV is unable to replicate in the mosquito and is digested in the mosquito’s gut.

For a disease to be spread by a mosquito, the virus or parasite must have been transferred to the mosquito after it bit an infected person or animal. These organisms can replicate in the mosquito and be transferred into a person through the saliva released at the bite site.

Unfortunately, mosquitos kill more people per year worldwide than any other animal/insect. Diseases transmitted by mosquitos include:

- West Nile virus

- Zika virus

- malaria

- dengue

- chikungunya

- yellow fever

……….

7. Can I be tested for bloodborne illnesses spread by mosquitos after I travel?

Yes. Testing for mosquito-borne illnesses can be performed at your doctor’s office. If you are experiencing symptoms that could indicate a mosquito-borne illness after traveling to regions with mosquitos, then you should see your doctor. Many of these symptoms are similar to the flu, such as fever, muscle aches, headache, eye pain or redness, joint pain and skin rash. Your doctor will take a travel history from you to determine what illnesses are common in the regions you visited and could cause the symptoms that you are experiencing. With this information, your doctor can then order the appropriate tests and, if needed, refer you to an infectious disease specialist. Note that people must never come to a blood center specifically to be tested for infectious diseases. This behavior decreases the safety of the blood supply and is not permitted.

…………..

Most of us have probably experienced multiple mosquito bites in our life. As I write this (while on a trip in China), I confess that I have over 10 mosquito bites that I am trying very hard not to scratch. This is despite having used insect repellant and some (but obviously not enough) protective clothing. These little buggers are tough. My blood type is O and mosquitos have always liked me. Meanwhile my travel partner, who has blood type A, has no bites.

(Sigh.) That stings a bit.