The Many Uses of Plasma

While plasma had been transfused as part of whole blood for hundreds of years, the specific value of plasma became acutely clear as a result of the devastating violence of WWII. Though plasma could not replace lost red cells and platelets, plasma and its related products were far easier to transport than whole blood (which was particularly important in battle zones) and was not only necessary for treating shock, but it was also found to help tide over the critically wounded soldiers and civilians until additional blood products became available.[1]

A huge investment in plasma — both in terms of research and collection infrastructure — was made during WWII, and it’s in part because of this investment that we have come to better understand plasma’s numerous lifesaving properties, and all the ways it can be used to save lives today.

What Is Plasma?

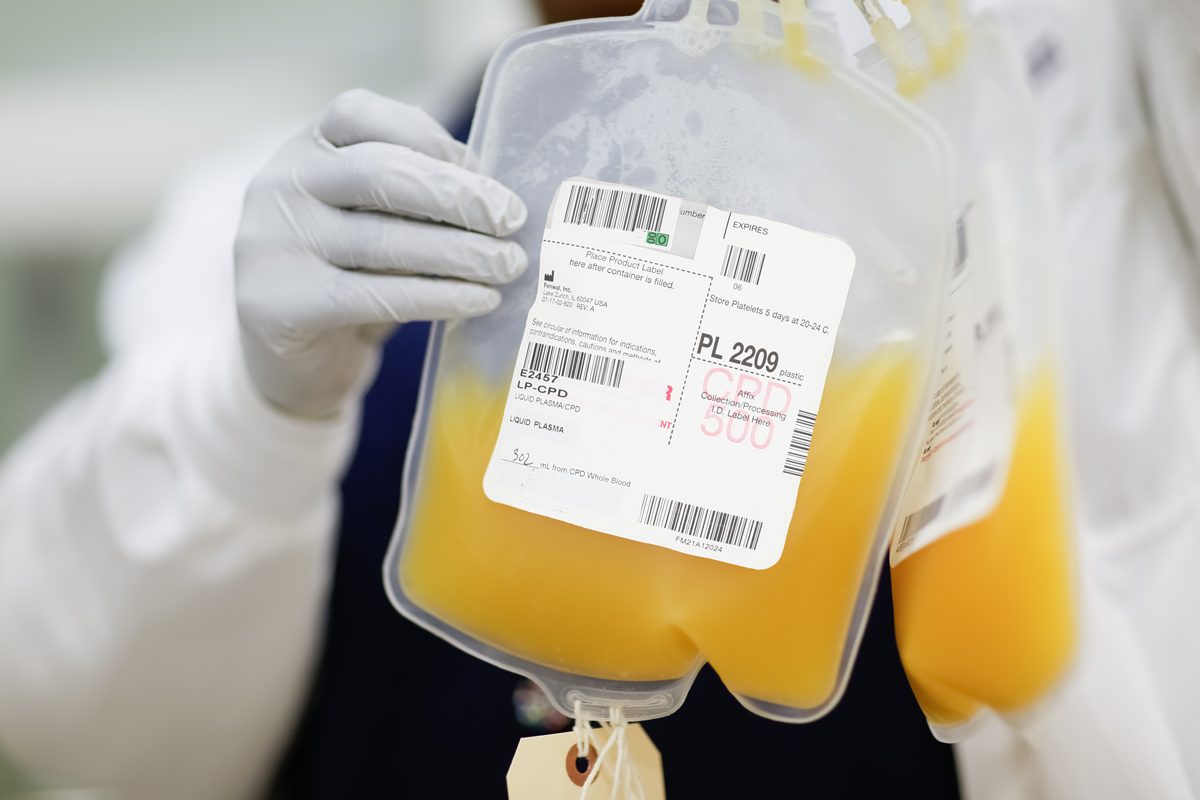

Plasma makes up the largest part of whole blood — about 55% by volume. Plasma is a yellowish liquid that carries waters, salts, proteins and blood components — including red blood cells and white blood cells —‑ throughout the body. Plasma contains important proteins such as clotting factors and fibrinogen, which play an important role in the body’s ability to stop bleeding when you have a wound.

Who Does Plasma Help?

During WWII, plasma was able to support so many people suffering from shock because of both its ability to replenish blood volume (since it makes up such a large portion of blood volume in healthy individuals) and because it helped to control bleeding. Today, plasma is still used in combination with other blood products to support those who have increased bleeding and have undergone shock. In settings where a significant amount of blood is needed due to a patient’s severe bleeding, studies show that early transfusion of plasma with red cells in similar ratios can improve the patient’s outcome. Plasma is also commonly used for those with serious burns and those with liver disease or other issues that could interfere with the body’s ability to produce certain factors that are found in plasma.

Donated plasma is matched to a patient based on their ABO group (without regard for – or +) and all types are needed since patients of all blood types require plasma, though types A and AB are most frequently transfused in emergencies since they are, in most cases, considered to be universally accepted by patients.

For more on how different plasma products support different types of patients, see the section below.

How Is Plasma Donated and Shared?

Plasma is a type of apheresis donation, meaning the donor gives blood with the help of a specific machine that draws out whole blood, centrifuges (i.e., spins to separate) it, retains the desired product (in this case, plasma), and then returns the other blood products back to the donor, all through the same needle. This allows us to collect a greater quantity of plasma without risking the health of the donor. A single donor can safely donate up to four units (pints) of plasma every four weeks due to its abundance in the body and ability to quickly replenish. Donating three units of plasma (which is average for a plasma donor) usually takes about an hour, during which time you’ll have access to SBC iPads for free entertainment!

SBC’s lab teams can create a number of plasma products from a plasma donation, based on the current patient need.

Frozen Plasma

Plasma collected from an apheresis (rather than whole blood) donation is typically frozen within 24 hours of collection to produce frozen plasma. Freezing plasma sustains high levels of clotting factors within the plasma for an extended period. Frozen plasma is thawed by hospital care teams before being transfused to the patient.

Plasma can also made from a whole blood donation by centrifuging (spinning) the whole blood to separate the plasma from the red cells. Plasma derived from whole blood can be stored frozen for one year or refrigerated for about one month.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is a product that contains specific plasma components, namely fibrinogen. Usually, patients who require cryoprecipitate have low fibrinogen levels due to blood loss, medication, genetic illnesses, for example, which can cause bleeding. To create cryoprecipitate, plasma is frozen, as the freezing process helps to activate the fibrinogen; then it’s thawed in the fridge and centrifuged to help separate out the precipitate. This precipitate is then resuspended in a small amount of residual plasma and then frozen again, this time, for storage. Typically, to create one adult dose of cryoprecipitate, you need to combine (“pool”) four to five individual units, so this “cryo pool” is the most common cryo product created. Cryoprecipitate can be kept frozen for one year, and then must be thawed before transfusing to a patient.

While regular plasma is helpful for both replacing blood volume and helping to stop bleeding, cryo, because it is concentrated, is used when the focus is controlling bleeding related to decreased fibrinogen levels.

Research

Medical and scientific researchers are always in need plasma from healthy individuals to enable their discoveries. Plasma has countless applications for researchers conducting studies to further patient care, many of which have to do with finding ways that frozen plasma can help to support trauma patients’ recovery when transfused early on in treatment.

Plasma is frequently used in research to characterize plasma treated cells in specific applications, for example in cytokine release and cell count viability. Currently, researchers in search of treatments and cures for serious diseases, such as autoimmune disorders and hemophilia, use antibodies and proteins found in human plasma to support their work. In addition, different types of proteins (including antibodies) and small molecules are found in human plasma that have the potential to be made into new and existing therapeutics.

Even more recently, convalescent plasma collected from donors who have recovered from Covid-19 is being studied and used as a therapy in patients with active infections.

Interested in donating?

If you want to learn more about plasma donation or set up a plasma appointment (you get a free t-shirt at your first donation!), please reach out to giveblood@stanford.edu or 818-723-7831. We’re always looking for more donors to join our plasma program!

REFERNCES

[1] Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce, Douglas Starr, March 2000